Proofs of Euler's formula

In this article we will see various ways to prove Euler's formula and Euler's identity.

Euler's formula

Euler's formula is:

Where θ is measured in radians.

Euler's identity

If we substitute a value of π for θ in we get Euler's formula:

Since cos π is -1, and sin π is 0, this leads to Euler's identity:

If we prove Euler's formula, this will also prove Euler's identity.

What do we mean by proof?

Quite often in mathematics, we might have an equation where the meaning of the equation is extremely clear, and we simply need to prove that it is true. This applies, for example, to Pythagoras' theorem - we know what a triangle is, and we know how to square and add numbers, so all we need to do is prove that the formula is correct.

With Euler's formula, things aren't quite so clear-cut. We are raising e to the power of an imaginary number. To take the naive definition of powers, we are multiplying e by itself an imaginary number of times. What does that even mean?

An alternative way to look at this is to say that we have decided to define Euler's formula to be true. The task now is to decide if that definition is a good one. Is it sensible, consistent, and useful to say that, by definition, Euler's formula tells us what it means to raise a number to an imaginary power.

Our approach will be to look at the formula from several angles. Firstly, we will consider the geometric interpretation of the formula, and how it relates to what we know about the modulus-argument form and multiplication of complex numbers. Secondly, we will look at several definitions of the exponential function for real numbers, and ask if Euler's formula appears to be correct when we extend those definitions into the imaginary domain.

We will see that it makes a lot of sense to accept Euler's formula as the definition of what it means to raise a number to an imaginary power.

Geometric interpretation of Euler's formula

Here is Euler's formula again:

The right-hand side has a simple geometric interpretation. Here it is represented on an Argand diagram:

The complex number with real part cos θ and imaginary part sin θ is a distance 1 from the origin and makes an angle θ with the x-axis. In other words, it has modulus 1 and argument θ.

If we multiply both sides of Euler's formula by r, where r >= 0, we get the following:

Here is that point on an Argand diagram:

The complex number with real part r cos θ and imaginary part r sin θ is a general complex number with modulus r and argument θ. So, based on the previous formula the expression:

Also represents a general complex number with modulus r and argument θ.

Multiplication

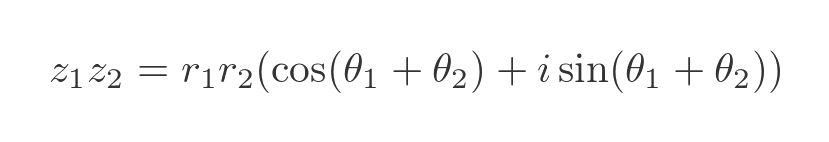

When we multiply two complex numbers in modulus-argument form, we multiply the 2 moduli, and add the 2 angles:

This is shown on an Argand diagram here:

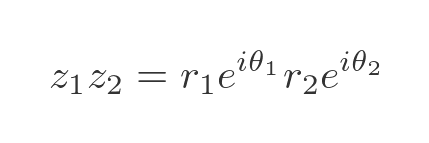

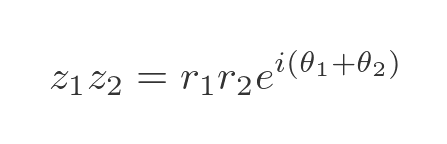

Using the exponential form gives:

When we multiply 2 exponential terms that have real exponents, we add the exponents. If we assume that imaginary exponents work in the same way, this expression becomes:

So we have multiplied the moduli and added the angles, which is exactly what we need. This shows that Euler's formula is consistent when we multiply two complex numbers. That is a good start, although it doesn't really explain why the exponent has a factor of i.

If you look at the modulus-argument article linked previously, you will see that Euler's formula is also consistent when raising a complex number to a real power, or finding a real root of a complex number.

Definitions of the exponential function

There are several ways to define the exponential function. We will look at 3 different ways here, and then go on to see if those definitions still make sense in terms of Euler's formula.

The first definition of the exponential function is that it is the only function f that satisfies these conditions:

This follows since the exponential function is the only non-trivial function that is its own derivative. Of course, if we multiply the exponential function by any real number n, the resulting function is also its own derivative. By specifying that the value of the function must be 1 when x is 0, we eliminate any n other than 1.

A second definition of the exponential function relies on a limit:

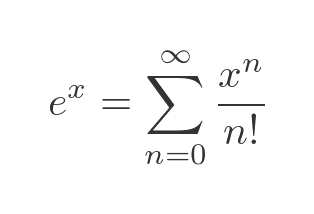

Finally, we can define the exponential function via its Maclaurin expansion:

Proof by differentiation

We saw previously that a defining characteristic of the exponential function is that it is its own derivative.

What about the derivative of e to the power of iθ? If that means anything, we would surely expect to be able to differentiate it in the normal way. So let's assume:

Notice the extra factor of i since the exponent is iθ (due to the chain rule). Just for good measure, as we will be needing this soon, here is the negative case:

We can now take Euler's formula:

And rearrange it:

This can be written as:

It is easy to verify that when θ is 0, this equation is true (e to the power 0 is 1, and cos 0 is 1).

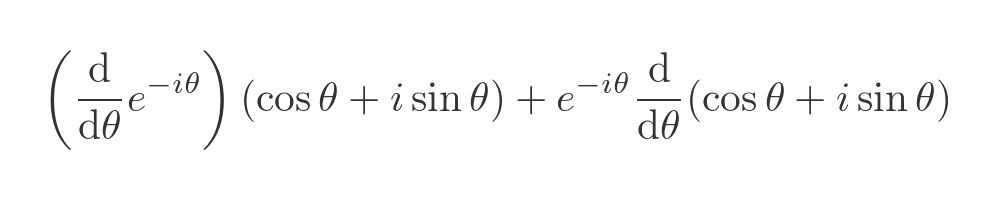

To prove that this expression is always equal to 1, we just need to prove that its first derivative is always zero. We will use the product rule to differentiate the LHS:

This gives:

Taking out the common exponential factor gives:

The sine and cosine terms sum to 0 (remembering that i squared is -1), so the whole expression is zero. This proves that Euler's formula leads to the result:

Proof by limit

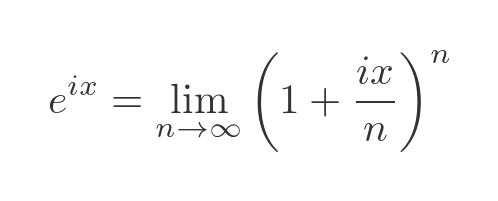

Now let's look at the second definition of the exponential function:

If this definition is valid for imaginary exponent we would expect that:

Again we will use Euler's formula to show that this result is valid, which again supports the validity of the formula.

We will start with DeMoivre's formula. Note that some proofs of DeMoivre's formula rely on Euler's formula, so that would make this a circular proof. However, there is a proof of DeMoivre's formula that doesn't rely on Euler's formula, so that is not an issue.

Now let's substitute x/n for θ:

Notice that the LHS is independent of n, therefore the equation is true for any n, including the limit as n tends to infinity:

Now as n gets very large, x/n gets very small. For very small values, cos(x/n) tends towards 1, and sin(x/n) tends towards x/n:

In that case, the limit can be written like this:

Using Euler's formula, this scan be written as:

Which again proves that Euler's formula is consistent with the limit form of the exponential function extended to the imaginary domain.

Proof by Maclaurin expansion

The Maclaurin expansion of the exponential function is:

We will substitute a value of iθ for x to extend this definition to the imaginary domain:

We can simplify this using the following identities:

Power of i from a repeating sequence of i, -1, -i, 1 ... Applying these identities to the equation above gives:

We can separate out the real and imaginary terms in this equation:

Let's compare this with the standard Maclaurin expansions for sin and cos:

The cos series is identical to the real series in the previous exponential function, and the sin series is identical to the imaginary part. So this proves once again that:

Summary

We have shown that Euler's formula is consistent with the way that complex number multiplication, powers and roots work. We have also shown that, for each of the 3 commonly used definitions of the exponential function, if we assume that the definitions can be extended into the imaginary domain, then Euler's function can be proved as a consequence of the definition.